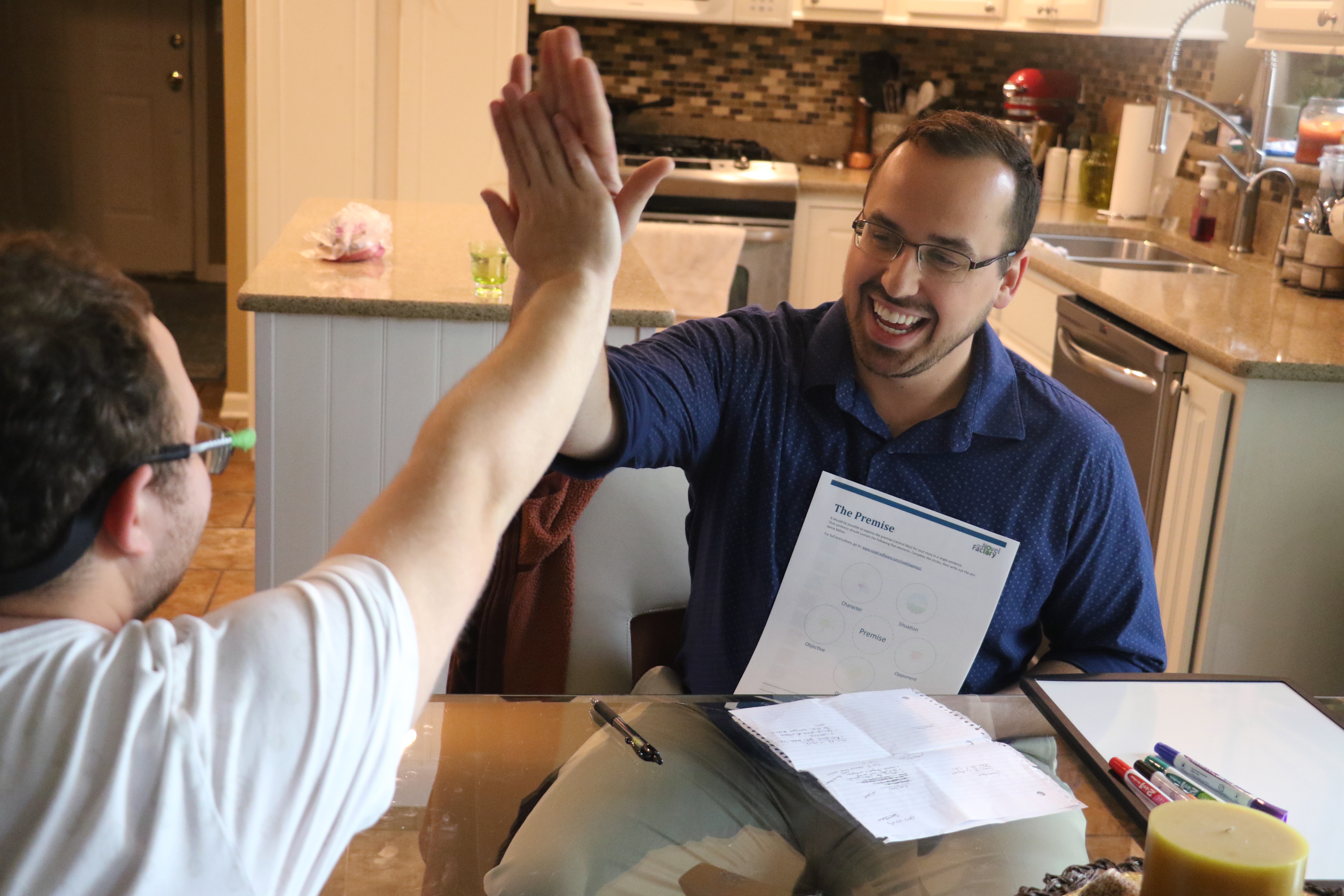

Tristen Ferran, 19, sits at a glass table in his family’s dining room across from his 28-year-old behavior consultant from ADEC, Ryan Gomez Wengerd. A big fluffy white dog is casually sprawled out on the floor nearby gnawing a dog bone.

“And the fifth and final one is a ‘Zinger’ zombie,” says Tristen, with the glimmer of a passionate storyteller in his eye.

“Alright,” Ryan says. “Gimme details, I’m in!”

“A Zinger is a zombie that fakes sleeping,” explains Tristen. “It fakes being dead, and then it wakes up and makes a ‘zinging’ sound, like ZZZZZ!”

“Ahh, okay, okay,” says Ryan, nodding his head as he jots down the details onto a worksheet to help organize Tristen’s wildly creative ideas.

It may sound like Tristen and Ryan are storyboarding ideas for a film or TV show, or preparing for a game of Dungeons & Dragons. In reality, Ryan is guiding Tristen—who has a disability—through a behavior therapy session.

“Behavior therapy often comes across as a negative thing to people, as if the goal is to punish or clamp down on so-called ‘bad behavior’,” explains Ryan. “The truth is that the behaviors are often just symptoms of a disability, and some folks just need a little guidance so that they can live better lives.”

“We have some fun ways of helping them get to where they need to be,” he adds with a smile.

Defying traditional roles

Ryan obtained his Bachelor’s degree in social work in 2013 and got a job at Oaklawn Psychiatric Center shortly thereafter. In 2015 he accepted a job offer from ADEC and, after obtaining his Master’s degree in 2018, stepped up to his current role as a behavior consultant in early 2019.

“I’m interested in human psychology and enjoy helping others achieve their goals,” says Ryan. “There is nothing more exciting than seeing someone overcome difficult challenges in their lives.”

Communicating effectively in situations involving direct conflict can be a challenge for anyone, let alone for an individual with a disability. Ryan explains that understanding emotions, maintaining healthy relationships, setting boundaries and developing healthy coping skills are topics he focuses on in his behavior therapy sessions with his clients, including Tristen.

Tristen’s intelligence and creativity are readily apparent, but Ryan explains that Tristen’s temper is one of his challenge areas being addressed in his therapy sessions.

In these sessions, Ryan discovered that acting out role-playing scenarios with Tristen was a powerful tool. In an average session, Ryan and Tristen may brainstorm a handful of scenarios where conflict may arise and role-play to see how the situations might play out in real life.

For example: Tristen may role-play as a restaurant patron and Ryan as a waiter. In the scenario, the waiter may accidentally spill an imaginary drink on the patron, forcing them to react to each other. After working through the scenario, Ryan and Tristen may switch roles so that Tristen can see the same situation play out from the other perspective.

In this way, Ryan can help Tristen work through emotions in a wide variety of tense situations in a safe environment where they can pace themselves and pause to reflect.

“In our sessions I learned that Tristen is a big fan of The Walking Dead,” says Ryan. “I saw an opportunity to engage with Tristen on that, because the human characters in that show are always caught up in intense interpersonal conflicts, and some approach conflict more wisely than others. So, in today’s session Tristen is probably going to be very excited to share the details of some of his own characters and storylines he’s invented to fill a similar imaginary setting that we will be able to use in our future role-playing sessions.”

In the session, Tristen is fully engrossed in dishing out the details of these characters and ideas that have been stewing in his mind since the previous session.

“I think we should get a sketch artist in on this and turn it into a comic!” he says excitedly.

Staying grounded

Other methods Ryan has found useful are techniques derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

In one method, Ryan deploys a technique to teach Tristen to use what he calls “I-statements” to express his feelings. With this technique, Tristen is encouraged to use statements like “I feel upset” or “I feel frustrated” to communicate his feelings to others, rather than resorting to verbal attacks.

In session, Tristen may start by formulating a non-confrontational I-statement, such as “I feel happy, because I got to watch some new TV shows this week”, but with some gentle encouragement he works his way up to I-statements involving conflict, such as “I feel mad when I get into arguments with my mom, because it’s unfair to her and myself.” According to Ryan, articulating his feelings helps him see the difference between what it means to express feelings versus simply acting out on them.

Another approach Ryan uses is a grounding technique which encourages an individual to divert their attention to something else by making lists in their mind when they are in the heat of the moment during an interpersonal conflict.

“This helps them take a step back from a conflict and stop to think first before reacting,” says Ryan.

While in session, Tristen explains that he has recently been watching another TV show called Atypical—a show featuring characters with autism spectrum disorders. He says that he was intrigued when he noticed one of the characters using the same grounding technique in the show.

“When some characters have trouble coping and have an attack, they do their coping skill automatically,” says Tristen. “I’m not there yet.”

Environmental awareness

Many can empathize with the notion that it’s one thing to practice communication skills and coping mechanisms in a controlled setting, but it’s another thing entirely to deploy them when you’re directly confronted with an actual conflict situation playing out in real time.

In his sessions with his clients—which usually take place on-site in the client’s home environment—Ryan talks about using what he describes as an “environmental perspective.” With this perspective, Ryan makes mental notes about the environments and people the client encounters in daily life and factors these observations into his approach toward individualized treatment.

“For instance, in some homes there may be certain environmental factors that provoke a client more than others,” explains Ryan. “Because our sessions are generally conducted in open environments, I try to model my own behavior and adapt environmental factors in helpful ways to form a space that meets the needs of the individual.”

“I also have to try to gain detailed insight into environments the client is exposed to elsewhere that I may never see, so that I can help the client make those connections,” he adds.

Ryan explains that one of his biggest challenges is getting a client to connect what they learn in their therapy sessions to their lives outside the sessions. The first time he saw Tristen connect his treatment to his daily life happened at school, when Tristen had to advocate for himself in a meeting with various school officials where Ryan was also present.

“I was really impressed by how he handled the situation,” says Ryan.

Reassuring parents and caregivers

With the negative associations with therapy, parents and caregivers may be wary of the service initially.

“Parents want to know that you’re trustworthy,” says Ryan. “To help reassure them, I would ask what kind of behavior change they would like to see at home, how I can help improve their lives, and most importantly get to know them personally.”

To be effective in his job, Ryan explains that he needs to make sure that parents and caregivers are on board with what he is doing. Getting to know them personally is one piece of that, and another piece is giving them a chance to see him in action. He recommends parents have a meet-and-greet session with him and says they can even sit in on the first session with their child if they want to.

Ryan explains that it is also important for him to show parents that the therapy is rewarding for the client. In the sessions, Ryan will reward clients with positive activities, such as playing a game, watching a video or going for a walk with the client after the session—he avoids using food or candy as rewards.

“If I’ve done my job, I’ve not only helped the client, but also engaged parents in the process so that the client can continue to receive the care they need when I’m not around,” he says.

In the end, Ryan says that helping others is a great way to see the world in a positive light.

“I get to share that experience with the people I serve and show them that someone cares.”